3. HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Kirkland and the Everest Neighborhood are located on the traditional land of the First Peoples of Seattle, the Duwamish People. The Duwamish Tahb-tah-byook tribe once inhabited the Lake Washington shoreline from Juanita Bay to Yarrow Bay, as described in more detail in the Community Character Chapter of the Comprehensive Plan. Lake Washington offered an abundance of riches, including wapatoes (a wetland tuber), tules, cedar roots, salmon, waterfowl, berries, deer, muskrat, beaver and otter. The 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott guaranteed hunting and fishing rights and reservations to all Tribes represented by the Native signers, including the Duwamish People. In return for the reservation and other benefits promised in the treaty by the United States government, the Duwamish People exchanged over 54,000 acres of its homeland. Today those 54,000 acres encompass much of present-day King County, including Kirkland. Unfortunately, the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in the early 1900s had a detrimental effect on the Duwamish People, lowering the level of the lake, affecting wetlands, and diminishing traditional food sources.

Before the Everest neighborhood became part of Kirkland in 1949, it served as a largely agricultural area providing fresh produce, dairy products, and eggs to Seattle residents.

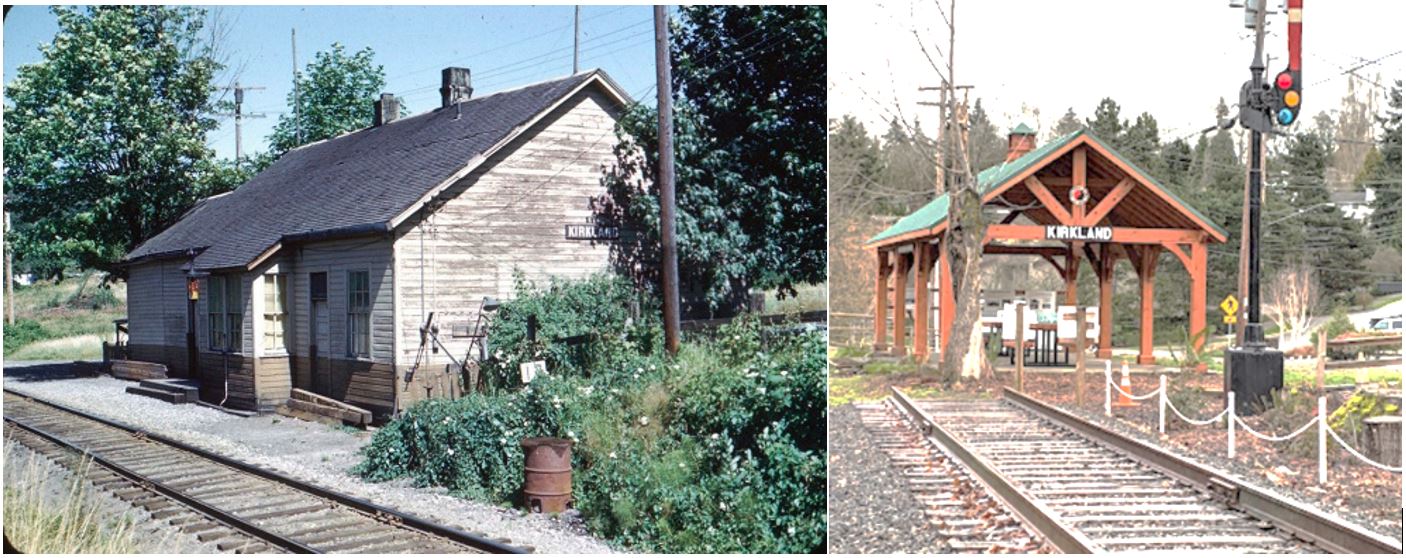

The Everest neighborhood was the railroad gateway to Kirkland. In the early part of the 20th century, goods and people primarily traveled over long distances either by ferry across the lake or by rail on the Lake Washington Belt Line, later the Northern Pacific rail line, along what is now the Cross Kirkland Corridor (CKC). Kirkland’s rail station was in the Everest Neighborhood, on Railroad Avenue, just south of the Rotary Central Station picnic pavilion. Vestiges of an older railroad right-of-way can be seen in the embankment in the woods directly to the east of Everest Park. This was the railroad built to serve Peter Kirk’s steel mill in the late 1880s. The embankment connects to the north with what is now Slater Street, which follows the route of this first railroad. The station was torn down in the late 1960s and was replaced by a metal building that remained into the mid-1970s before being demolished. The concrete slab for the metal building now serves as the concrete foundation for the Rotary Central Station picnic pavilion.

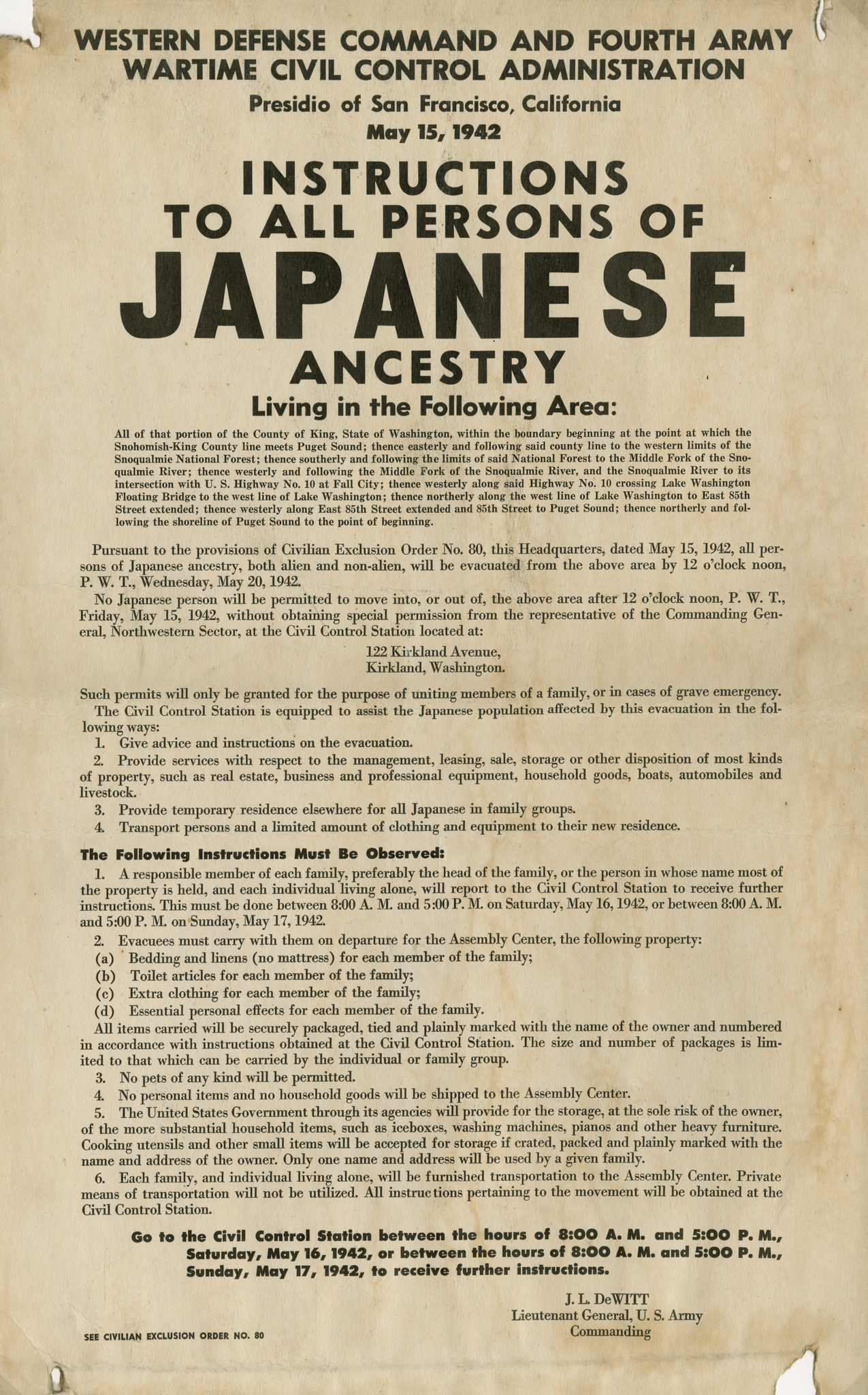

The train station’s history is also a painful reminder of the forced relocation of people of Japanese heritage living along the west coast to internment camps during World War II. According to the U.S. Government War Department, Civilian Exclusion Order No. 80 dated May 15, 1942, on May 20-21, 1942, persons of Japanese ancestry living in Kirkland and other parts of the region were required to leave all their personal property and evacuate the area via boarding the train in Kirkland to relocate to inland detention camps located elsewhere in the United States (see photo of the poster documenting the government order below).

The existing Rotary Central Station building was completed in 2020 with private and public contributions and volunteers as a tribute to the City’s railroad heritage and historic station location. The Rotary Central Station pavilion contains picnic tables, illustrative signage about history in Kirkland, a train signal, old rail tracks and native vegetation along the CKC. The railroad history theme continues at the Feriton Spur Park, located a short walk south of the Station building along the CKC, where an old train caboose has been repurposed for other uses.

Everest Park and the neighborhood are named after Harold P. Everest (1893-1967), former Chairman of the Journalism Department at the University of Washington, owner and publisher of the East Side Journal, and civic leader in Kirkland. In the 1940s, Everest Park was the site of a housing project, called ‘Project A’, built to house U.S. Government wartime emergency workers at the Lake Washington Shipyards, where Carillon Point is today. Following World War II, workers left the area as shipyard work disappeared and the housing project was torn down when the residents left. The Federal government sold the land to the City for a park for fifty percent of its true value. It is believed that a few of the houses were moved to various nearby locations. The original baseball field was completed in June of 1963. Everest Park has existed for close to 65 years undergoing several changes and continuing to evolve today.

The industrial area between the CKC and 6th Street South evolved from a heavy manufacturing area to high technology and other office uses. During World War II, a warehouse complex was built for the U.S. Navy and the shipyard adjacent to the railroad tracks in the industrial area between 6th St South and the tracks. After the war, these buildings became headquarters for a number of manufacturing companies including the Seattle Door company. Into the 1970s, Seattle Door was Kirkland’s largest employer, with several hundred workers at the site. In 2006, the old buildings were torn down and the site redeveloped into the Google office complex. Through a private/public partnership with the City and a developer, Feriton Spur Park was constructed along the CKC providing amenities for the community such as public open spaces, basketball courts, tennis courts, other recreational facilities, restroom, and a community garden.

Old train station and new Rotary Central Station picnic pavilion

Policy EV-1:

Preserve features and locations that reflect the neighborhood’s history and heritage.

As described above, Everest has a rich history. The Rotary pavilion, which conveys the story about the old railroad depot located along the CKC, and the sign at the railroad trestle, are great examples of what can be done to provide an amenity for the community and at the same time tell the history of an area. At this time, there are no buildings, structures, sites or objects in the Everest neighborhood listed on the National and State Registers of Historic Places or designated by the City of Kirkland. The City should continue to periodically survey buildings in the neighborhood to identify and designate those of historic significance.

Policy EV-2:

Provide markers and interpretive information at historic sites.

Providing markers and interpretive boards enables the community to have a link with the history of the area. Attention should be given to celebrating the neighborhood’s history in an inclusive way, including helping residents and visitors understand the history of the people who lived in the area before the early pioneer settlers.