Chapter 18.90

DESIGN GUIDELINES*

Sections:

Article I. Introduction

18.90.010 Preface.

18.90.020 Heritage preservation in Skykomish.

18.90.030 The historic commercial district.

18.90.040 Landmark properties.

18.90.050 Design review in Skykomish.

Article II. Design Traditions

18.90.060 Design traditions in Skykomish – Historical development of the town.

Article III. Design Guidelines

18.90.070 General design guidelines.

18.90.080 Guidelines for commercial development.

18.90.090 Guidelines for residential development.

18.90.100 Guidelines for institutional development.

18.90.110 Guidelines for other site work.

*Code reviser’s note: Appendices A, B, and C referenced in this chapter may be found on file in the office of the town clerk.

Article I. Introduction

18.90.010 Preface.

(1) This booklet is the official set of design guidelines for the town of Skykomish. The guidelines were adopted on December 1996 by the Skykomish town council. Now and in the future, these guidelines will serve as a tool in the community-wide effort to celebrate the distinctive character and rich railroad heritage of Skykomish.

(2) Design review is built into the town’s existing development review process. The guidelines work in tandem with Chapter 18.45 SMC. Using these guidelines as criteria for review, a citizen design review board meets with all interested applicants to discuss proposed projects.

(3) A formal design review is mandatory for all exterior projects in the historic commercial district, and for all projects affecting landmark properties. For properties in residential use, compliance with the findings of the design review board is voluntary on the part of the applicant. For properties in commercial or public use, and for all landmarks compliance is required.

(3) Although the design guidelines focus primarily on designated landmarks and properties within the historic commercial district, they are also intended as a helpful reference for projects throughout the community. The overall goal of the guidelines is to encourage careful change over time – change that respects and protects the unique visual quality of historic Skykomish. (Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.020 Heritage preservation in Skykomish.

(1) Recognizing a Unique Heritage. The town of Skykomish, Washington, the western gateway to the Cascade Division of the Great Northern Railroad, is steeped in history. The physical fabric of the community today is a tangible reminder of its colorful past. Residents and visitors alike sense its history in the dramatic mountain setting, in the way the town straddles the railroad tracks, and in the picturesque, false-front commercial buildings along Railroad Avenue. These historic resources are powerful illustrations of the community’s roots in railroading, saw-milling, mining, and forestry.

(2) Historic preservation activity began in Skykomish as early as 1976, when Railroad Avenue was surveyed and entered into the King County Inventory of Historic Sites. The 1978 community development plan for Skykomish stressed the importance of preserving certain significant buildings. In the early 1980s, owners of the Skykomish Hotel received community development block grant funds through the King County historic preservation program for exterior rehabilitation of the hotel. Despite these early efforts, the town subsequently suffered the loss of some key historic buildings.

(3) Planning for Preservation. Skykomish formally acknowledged the value of its heritage in the Skykomish comprehensive plan (February, 1993). The plan set forth goals and objectives that support retaining a quality of life unique to Skykomish, including its sense of history.

Goal 14, Objective 14.2:

The preservation of the history is important to maintenance of the “small town quality of life.” The history of the community is told in its people and in its buildings. The Town should implement a program to identify and preserve buildings and structures of historic value.

(4) Tourist activity was identified in the comprehensive plan as a primary element of the town’s economic development strategy, and historic resources were noted as an asset to economic growth. The comprehensive plan named historic Railroad Avenue as the “centerpiece of the community,” and recommended that tourist-related business along that street be encouraged. To achieve these goals, the comprehensive plan further recommended that the town implement regulations through the zoning ordinance.

(5) Success in the 1990s. Skykomish citizens joined together in the mid-1990s to launch a multi-faceted program of heritage preservation. The Skykomish Historical Society was established for the purpose of researching the town’s past, collecting historical documents and photographs, and increasing awareness of local heritage. In the spring of 1995, the town of Skykomish created an historic commercial district by zoning ordinance. To protect the special character of the historic district over time, the ordinance required that proposed changes within the district be monitored by a local design review board.

(6) Concurrently, Skykomish established a landmark designation program in conjunction with the King County landmarks and heritage commission. Skykomish Historical Society members, local students, and other volunteers conducted a community-wide survey of historic properties during the summer of 1995. By the spring of 1996, five of the most significant historic properties in Skykomish were designated as local landmarks.

(7) Over the past five years, the framework for effective heritage preservation in Skykomish has been put in place through the dedicated efforts of local citizens. Such mechanisms will help to shape Skykomish in the 21st century. These design guidelines are the latest tool in a community-wide effort to protect the distinctive heritage of Skykomish in the years to come. (Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.030 The historic commercial district.

(1) Creating an Historic District. Section 3.9 of Skykomish Zoning Ordinance No. 235 (Chapter 18.45 SMC), adopted in April of 1995, created an historic commercial district with Railroad Avenue at its core. The ordinance cited two purposes:

(a) To encourage the preservation and restoration of historic structures within the town of Skykomish, recognizing that they are valuable assets, both economically and aesthetically, to the town and its citizens.

(b) To increase awareness and appreciation for the historic heritage of Skykomish, and its role in the westward expansion of the Great Northern Railroad.

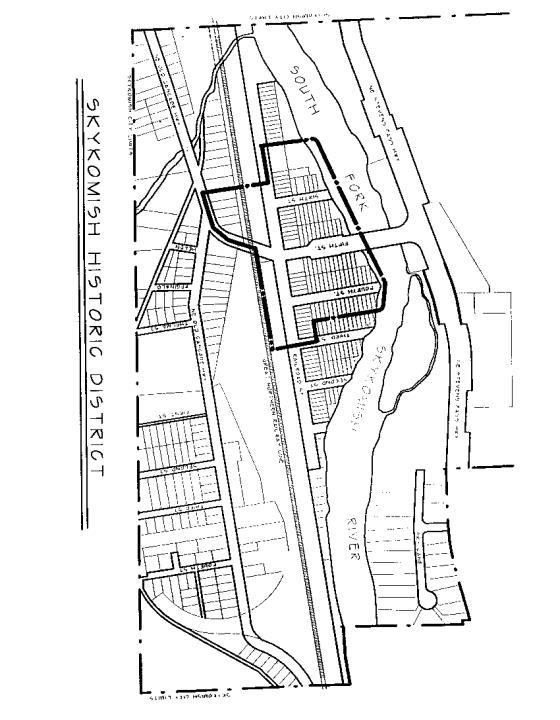

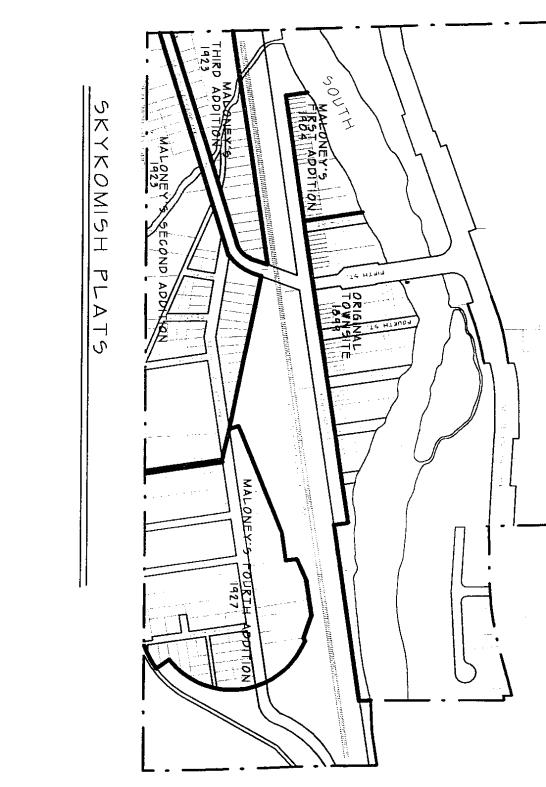

(2) What is Included within the District. The historic commercial district currently includes most of the original plat of Skykomish, where the greatest concentration of historic structures exist. Within the district is a rich mix of commercial structures, several single-family residences, and various public and institutional buildings.

(3) Its boundaries run from the school yard on the west along Railroad Avenue to Third Street on the east, and from the school yard east to Fourth Street along the bank of the Skykomish River. South of Railroad Avenue, the district contains the depot and the park, as well as the library to the Masonic Hall along the Old Cascade Highway.

(4) Development Standards within the District. Chapter 18.45 SMC consists of property development standards (SMC 18.45.060) and performance standards (SMC 18.45.070) which set basic lot size, lot coverage, building height, and setback requirements for the historic commercial district. These standards also prohibit certain types of structures in the district, and provide broad guidelines for compatibility of new construction with existing historic character. In a general way, the standards address landscaping, fencing, trash receptacle, street furniture, exterior mechanical devices, antennae, outdoor storage, outdoor lighting, and detached accessory buildings.

(5) These design guidelines reinforce the property development and performance standards of this zoning title. The design guidelines are intended to clarify and supplement those standards, and do not replace or supersede them. (Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.040 Landmark properties.

(1) Interlocal Agreement. Landmark designation in Skykomish began in 1995, when the town entered into an interlocal agreement with King County. Under this agreement, the King County landmarks and heritage commission, through its established criteria and procedures, designates historic buildings, districts, and sites within the town limits of Skykomish. Attractive incentives are then made available to the owners of these properties through King County. These incentives include technical assistance and monetary grants for restoration or rehabilitation.

For its part in the interlocal agreement, Skykomish enacted Ordinance No. 244, proclaiming its intent to foster civic pride and promote local tourism through the preservation of significant places in the community. The town of Skykomish design review board was also established by the ordinance codified in this chapter, in order to provide a mechanism to protect designated landmarks from loss of historic “integrity,” or character.

(2) Designated Landmarks. Presently, five properties in Skykomish have achieved landmark status. With the exception of the depot, all have received grant funds for historic preservation through King County. The current landmarks include the Maloney General Store, the Skykomish School, the Teachers Cottage, the Great Northern Depot, and the Masonic Hall.

(a) Maloney General Store: Prominent wood-frame commercial structure fronting the Great Northern tracks on Railroad Avenue. Built in 1893 by the founder of Skykomish, John Maloney. Served as the community’s general store and post office for more than 50 years. Various additions and alterations over the years.

(b) Skykomish School: Three-story concrete building in the Art Moderne style, funded by the WPA. Designed by architect William Mallis in 1936, still serving its original function as a public school for grades K through 12 and a community center. Interior features original spaces, finishes, built-in cabinetry, blackboards, and clocks.

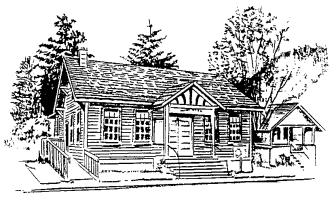

(c) Teachers’ Cottage: Built by the school district circa 1910 to house its female teachers. Craftsman style detailing, with multi-paned window sash and cross-gabled roof faintly Tudor in flavor. Interior retains original staircase, built-in cabinetry, woodwork, and light fixtures.

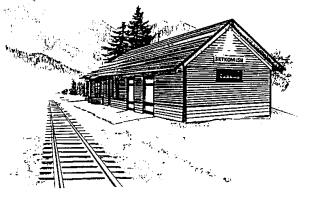

(d) Great Northern Depot: The symbolic heart of Skykomish, built in 1894 as a passenger depot on the south side of the tracks. Relocated in 1922, reoriented and expanded with addition of large freight room at east end. Gabled, wood-frame structure with lapped siding and projecting bay window for station operator facing tracks. Interior features original ticket window and office, and some original finishes.

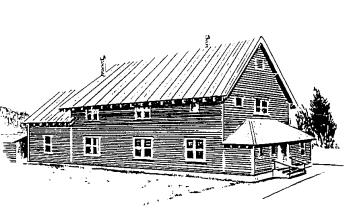

(e) Skykomish Lodge #259/Masonic Hall: Home of the oldest and only surviving active fraternal organization in Skykomish. Sturdy frame, gable-roofed building completed in 1924 by local Masons, reflecting the combined skills of railroad employees, mill workers, and businessmen. Still serving as a community focal point.

(3) Potential Landmarks. Other properties in town that best illustrate the industry, commerce, and social history of Skykomish have been identified as potential landmarks. Some of these are the Town Hall, the Skykomish Community Church, and the Skykomish Hotel. Over time, members of the Skykomish historical society and the design review board will work with local property owners to inform them of the incentives and advantages associated with landmark designation.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.050 Design review in Skykomish.

(1) What is Design Review? Design review is a tool to preserve and enhance community identity in the face of change. Every small town faces threats to its quality of life, whether in the form of growth, stagnation, modernization, or accommodations to the automobile. Sometimes unwanted change occurs incrementally, project by project, building by building. In towns like Skykomish with a unique railroad heritage, larger threats may include the wholesale demise of a primary economic activity.

Community identity can be synonymous with historic character. Protecting the visual remnants of the past links a town with its reason for being, and with the efforts and aspirations of the people who built it. Historic preservation makes environmental sense in that all residents benefit from visual quality in their daily lives. Preservation also makes very good economic sense – towns with historic character draw new businesses, attract tourism, and improve property values.

Change is a given. Through design review, the town of Skykomish seeks to encourage sensitive and appropriate change within its historic commercial district, and to encourage new construction that respects the traditions of the past.

(2) Review and Compliance. In Skykomish, design review is built into the existing development review process. Under this zoning title, a design review board is empowered to approve all building and renovation plans within the historic commercial district. Under Chapter 15.15 SMC, the design review board is charged with approving proposed changes to designated landmarks.

The Skykomish design review board consists of three regular volunteer members, appointed by the mayor. The board meets on a regular basis, and members of the general public are welcome to attend and participate. Using these design guidelines, the board reviews proposed projects in the presence of the applicant. Through open discussions, the board offers advice and assistance on ways to accomplish the project, within budget, in a manner that meets the guidelines and protects the overall historic character of Skykomish.

A formal design review is mandatory for all exterior projects in the historic commercial district, and for all projects affecting landmark properties. For properties in residential use, compliance with the findings of the design review board is voluntary on the part of the applicant. For properties in commercial or public use, and for all landmarks, compliance is required.

(3) What Projects Require Design Review? The design review procedure is required for the types of projects listed in subsections (4) and (5) of this section, whether or not a building permit is issued.

(4) Projects in the Historic Commercial District Require Design Review. Compliance with the findings of the design review board is mandatory, except for residential use.

(a) Exterior alteration to existing buildings:

(i) Replacement, removal, addition of architectural features;

(ii) Repainting, residing, reroofing;

(iii) New additions;

(iv) New secondary structures;

(v) Change in signage, new signage;

(vi) Demolitions, partial or whole;

(vii) Site work, including fencing, landscaping, disk antennas, screening for trash receptacles, and detached sheds.

(b) New building construction.

(c) Relocation, into or out of the district.

(d) Demolition.

(5) Projects involving designated landmarks, whether inside or outside the historic commercial district, require design review. Compliance with the findings of the design review board is mandatory.

(a) Exterior alteration, including:

(i) Replacement, removal, addition of architectural features;

(ii) Repainting, residing, reroofing;

(iii) New additions;

(iv) New secondary structures;

(v) Change in signage, new signage;

(vi) Demolitions, partial or whole;

(vii) Site work, including fencing, landscaping, etc.

(b) Interior alteration of designated interior spaces.

(c) Relocation.

(d) Demolition.

(6) How the Guidelines are Organized. The Skykomish design guidelines are organized into five sections (SMC 18.90.070 through 18.90.110). The first (SMC 18.90.070) presents broad guidelines which address change within the historic district, and these are generally applicable to all projects. The next three sections (SMC 18.90.080 through 18.90.100) present guidelines for projects according to property type: commercial, residential, and institutional. A fifth section (SMC 18.90.110) covers minor kinds of site work such as landscaping, fencing, and secondary structures. Applicants may readily refer to the section which applies to their project.

Within each section, the guidelines are grouped according to the nature of the project: alterations to existing historic properties (over 40 years of age), alterations to existing nonhistoric properties (under 40 years of age), and new construction. Each guideline, in turn, is presented in bold type, with further explanatory language, or subguidelines, in regular type.

For a more complete description of the design review process in Skykomish, see Appendix A, on file in the town clerk’s office. (Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

Article II. Design Traditions

18.90.060 Design traditions in Skykomish – Historical development of the town.

(1) Summary History. The town of Skykomish is situated in the upper Skykomish River Valley on the steep western slopes of the Cascade Mountains. For centuries, the surrounding mountains and river valleys were inhabited by the nomadic “Skykomish,” meaning “inland people.” It was not until 1893 that a permanent settlement was established as a division point on the newly-laid lines of the Great Northern Railroad.

By the turn of the century, the village boasted a population of 150, a shingle mill, saw and planing mill, hotel, school, and general store. The town suffered a major fire in its commercial district in 1904, but was quickly rebuilt. Mining and logging flourished in the surrounding forested environs, and the area became known at an early date for its fine fishing and hunting.

In the 1920s, Skykomish reached its peak population and bustled with activity. Construction of the Great Northern’s famous eight-mile tunnel over Stevens Pass drew hundreds of workers into town. The Bloedel-Donovan Sawmill and the rail yard were both greatly expanded. In conjunction with the new tunnel, the railroad electrified its line from Skykomish to Wenatchee. For the next 25 years, Skykomish served as the helper station where electric engines replaced steam locomotives for the uphill climb eastward over the summit and down into Wenatchee.

In later decades, the town’s population dwindled as local employment in the railroad and lumber industries declined. Activity in the Skykomish yard began to slow in the 1940s. The roundhouse burned down in the early years of World War II and was never rebuilt. Steam locomotives disappeared from the yard in 1953, and the electrics followed in 1956. Bloedel-Donovan sold the sawmill in 1946, and the business was gradually phased out. The town entered a period of economic retreat.

Growth in the cities on Puget Sound supported a gradual renaissance in the Cascade Mountains in the 1960s and 1970s. Stevens Pass Ski Area was greatly improved and enlarged. Recreational use of the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest increased and today there is growing interest in the railroad history of the greater Stevens Pass area. A number of Skykomish residences have been purchased by urbanites for use as ski cabins and weekend retreats. Several businesses in town cater to travelers and recreationists.

Because of geographic, economic, and environmental constraints, the population of Skykomish is not expected to increase dramatically in the near future. Soil permeability is not suitable for on-site septic systems, and little new multifamily or commercial development is possible until the sewer system problem is resolved. The economy of the community, however, is forecasted to grow, as recreation and tourism in the region expand.

|

Highlights in Skykomish’s History |

||

|---|---|---|

|

1890 |

– |

John Maloney staked first claim |

|

1893 |

– |

First permanent white settlement |

|

1899 |

– |

Town of Skykomish plat filed |

|

1900 |

– |

Skykomish Timber Company incorporated |

|

1904 |

– |

Maloney’s First Addition |

|

|

|

Fire burned much of commercial district |

|

1909 |

– |

Town incorporated |

|

1922 |

– |

Great Northern depot moved across tracks to present location |

|

1923 |

– |

Maloney’s Second and Third Addition |

|

1925 |

– |

Stevens Pass Highway opened over the summit |

|

1927 |

– |

Maloney’s Fourth Addition |

|

1939 |

– |

Skykomish River Bridge built |

|

|

|

Stevens Pass Highway relocated to north side of river |

|

1953 |

– |

Last steam locomotive |

|

1956 |

– |

Last electric locomotive |

(2) Physical Evolution of the Town. The railroad town of Skykomish was founded by John Maloney, a midwest farmer-turned-prospector. Through his association with railroad location engineer John F. Stevens, Maloney knew the precise route the Great Northern line would take through the Skykomish River Valley. Late in 1890, Maloney staked his claim on the flats of the South Fork in Section 26, Township 26 North, Range 11 East. Here a rail siding was constructed and, for a few years during construction of the line, the place was known as Maloney Siding. Soon after the rails were joined at Scenic in January of 1893, John Maloney built a general store and post office on his property, facing the tracks.

The settlement grew steadily in its formative years, serviced by the railroad. In August of 1899, John Maloney and his wife Louisa Fleming filed a plat of the town of Skykomish. The original townsite lay between the river to the north and the railroad tracks to the south, and extended from First to Sixth Streets. Oriented to the tracks, along Railroad Avenue, commercial businesses sprang up in the usual fashion of railroad towns. In the blocks adjacent to the downtown, modest wood-frame homes were built.

The Maloneys made subsequent additions to the town over the next three decades, each plat shaped by the river, the evolving Cascade Highway, and the expanding rail yard. Maloney’s First Addition, fled in 1904, subdivided the land west of Sixth Street to Seventh along Railroad Avenue. This plat laid out parcels for the school district where the present-day Skykomish School, teachers’ cottage, and playing fields still stand.

Maloney’s Second Addition, filed in 1923, extended the town south of the railroad tracks along the proposed Cascade “Scenic” Highway (at that time still a county road) east to include what is now the U.S. Forest Service compound. Maloney’s Third Addition, filed the same year, was also along the new highway, extending west to the Bloedel-Donovan Sawmill right-of-way. In 1927, a Fourth Addition was accepted, this one pushing the town limits east along the highway from First to Fourth Streets and beyond. Southwest of town, a distinct neighborhood known as Mill Town grew up after 1917 around the Bloedel-Donovan Mill, but it remained outside the town limits.

Both auto-oriented commercial development and residential growth occurred along the Cascade Highway south of the tracks in the 1920s and 1930s. Very little residential or commercial development occurred north of the river, however, until the old alignment was abandoned and the new Stevens Pass Highway (U.S. Highway 2) completed on the north bank. In 1939, the state of Washington erected the Skykomish River Bridge to connect the town with the new roadway.

(3) Neighborhood Character, Then and Now.

(a) Commercial Character. The first commercial developments in Skykomish sprang up between Fourth and Sixth Streets on Railroad Avenue. These were oriented to the south, facing the railroad’s main line, a siding, and the local depot. Historic photographs of the community tend to focus on views of Railroad Avenue, thus providing many important clues to the early visual character of the small downtown. Typical views through the 1920s depict muddy unpaved streets with raised plank sidewalks, modest wood-framed false-fronted shops, awnings or shed-roofed porches overhanging the boardwalks, and a streetscape dominated by the imposing four-story, hipped-roof Skykomish Hotel and the boomtown facade of John Maloney’s General Merchandise.

In the later years of World War I through the 1920s, a booming economy in Skykomish resulted in the growth of the business district and, to some extent, its spill-over to the early alignment of the Cascade Highway south of the railroad tracks. Auto-related commerce on the Cascade Highway in 1925 included an “office and auto supplies” store almost opposite the Masonic Hall, a 16-car garage with a repair shop behind it just east of that, and across Maloney Creek, a gas and oil station with a detached auto parts shop.

Following the re-alignment of the Stevens Pass Highway to the north of the river in 1939, commercial activity catering to passing motorists shifted across the Skykomish River Bridge. Most of the surviving business buildings there today are auto-oriented and appear to post-date 1955. South of the river and the railroad tracks, almost all signs of former roadside business have disappeared from the Old Cascade Highway.

By contrast, the original Railroad Avenue business district still conveys much of its early 20th-century character, despite two major fires. Local commercial design traditions can be readily seen in surviving early buildings, including the John Maloney Store, the Skykomish Hotel, McEvoy’s “Olympia” Tavern (now the Whistling Post), and several others. Typical features include wood-frame construction, hipped or gabled roofs, false-front facades, horizontal wood siding, wooden double-hung sash at the upper stories, and shop-front display windows with large multiple panes at street level.

Commercial buildings along Railroad Avenue have maintained the traditional zero setback from the street. Sidewalks are sheltered by shed roof overhangs or balustraded balconies with chamfered wood posts. Typically, auto parking occurs along the street and no off-street parking is provided. All of these attributes enhance the pedestrian-friendly quality of the commercial district where cars have not been allowed to dominate.

(b) Residential Character. Residential blocks developed along with the town’s platted additions, beginning with neighborhoods east of downtown and west of the school. Later residential districts rose up south across the tracks in both directions along the Cascade Highway. The housing stock of Skykomish was always modest, consisting mostly of single-story, wood-framed dwellings with hipped or gabled roofs, milled horizontal siding, and simple front porches with decorative Victorian or Craftsman-style trim. Building materials were readily available locally. Only one fancy house is mentioned in early descriptions, that of George Farr, Skykomish Lumber Mill manager, under construction in 1905 for a cost of $2,000.

Despite the influence of the mill and the railroad in town, most homes were privately built and owned. There were, however, some important exceptions. One distinctive neighborhood of railroad housing grew up along both sides of the tracks just to the west of downtown. All of these dwellings faced the tracks with streets at their back doors. A number of these houses still survive, including a substantial two-story home provided by the railroad for the section foreman. In 1918, Bloedel-Donovan erected a series of company-owned bungalows along the Cascade Highway through town. These were at first leased to employees, and later made available for purchase. Five of these look-alike dwellings remain standing today, some in relatively unaltered condition.

The residential character of Skykomish today reflects its railroad and mill-town roots. Domestic design traditions which have carried through to the present include wood-frame construction, gabled or pyramidal roofs, lapped or novelty siding, simple raised front porches – either full-width or entry – with hipped, gabled or shed roofs, wooden porch posts and balustraded railings, double-hung wooden window sash with vertical proportions, centrally-placed paneled front doors with windows, and wooden bracket details at rooflines.

Houses in Skykomish have maintained the traditional orientation to the street or to the railroad tracks, and are typically set back across a simply landscaped front lawn. Fencing and perimeter lot landscaping occurs, but is not common. Cars are parked either along the street or in detached wood-frame garages well set back behind houses. While not all neighborhoods have sidewalks, pedestrian circulation is simple and safe.

(c) Institutional Character. Public and institutional buildings in Skykomish were built in amongst the commercial and residential neighborhoods. The school and its manual training building, the depot, the Town Hall, the Masonic Hall, the Community Church, and the USDA Forest Service complex were all in place by 1940. Whether by location, scale, or design, all of these properties served as visual focal points in the community. Form varied as widely as function. All except the concrete Skykomish School in its streamlined Art Moderne style were simple, utilitarian buildings of wood-frame construction. Most exhibited some elements of Craftsman style detailing prevalent in the 1910s through 1930s.

Another highly visible area of the town well into the 1940s was the rail yard. A 1915 photograph shows a small wood-frame depot, four main tracks, and a siding past the water tower and oil shed. Pedestrian access across the tracks from the depot to Railroad Avenue was little more than a planked and graveled pathway. In 1922, the depot was moved to its present-day location and expanded with the addition of a freight room. New tracks were laid, and the old roundhouse replaced with a 16-stall facility. A giant new turntable was constructed, as well as new water tanks, oil tank, and a pump house.

Soon afterward, the Great Northern made preparations at the Skykomish yard for electrification of the line from Skykomish to Wenatchee. In late 1926, a large substation of concrete post and pier was erected south of the tracks near the earlier site of the depot. The substation featured massive areas of glazed industrial sash, a gabled roof with a monitor and, inside, equipment to convert electrical voltage and frequency for use by electric engines bound for Wenatchee. The substation was a familiar and symbolic Skykomish landmark until its removal in the 1990s.

Today, all of the historic rail yard structures with the exception of the depot have been removed by the Railroad. Other public buildings mentioned above, however, remain functional and relatively unchanged. Together they add texture and interest to the town’s stock of historic buildings. The school and the depot both enjoy a landscaped setting. At a fairly early date, a small park was created by the Great Northern just west of the depot. Today this attractive green space is maintained by the Skykomish Lion’s Club. Some landscaping was originally established along the front of the school on Sixth Street to soften the austerity of the building’s style. The plant materials have since changed, and the landscape is now informal, as are the settings for the other public buildings in Skykomish.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

Article III. Design Guidelines

18.90.070 General design guidelines.

(1) Overall Goal. The primary design goal for the town of Skykomish is to maintain its unique visual character through the preservation of its railroad setting, its pedestrian-friendly scale, and its historic building fabric.

(1) Guidelines. This section of guidelines applies to all projects within the historic commercial district and all designated landmarks. The guidelines are presented as broad concepts in bold type, with explanatory subguidelines below.

Guidelines in this section begin with the letter “G” to indicate that they are general standards that apply to all types of projects.

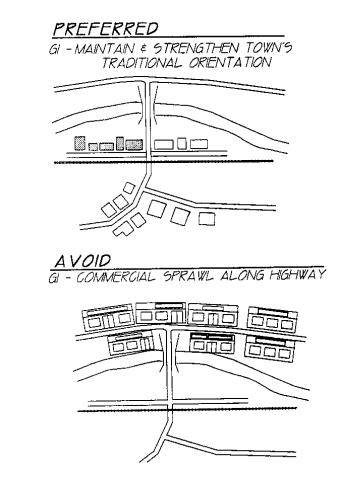

G1 Respect the historical town plan.

• Maintain the early layout of the community as defined by topography, the river, the railroad, and the Old Cascade Highway.

• Protect and strengthen the town’s traditional orientation to the railroad right-of-way, rather than to U.S. Highway 2.

• Preserve the historic block and lot pattern as established by Maloney’s original plat of Skykomish and its later additions.

G2 Reinforce pedestrian circulation.

• Continue the traditional use of covered sidewalks on Railroad Avenue.

• To encourage walking, establish sidewalks or graveled pathways where none exist.

• Consider establishing some pedestrian linkage across the railroad tracks.

• Look for opportunities to create safe pedestrian access to the river.

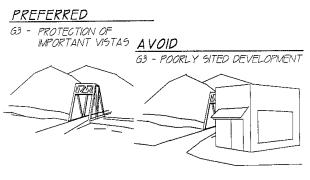

G3 Protect and enhance natural views, street vistas, and open space.

• Site new development so as not to obstruct views of the forested mountain setting.

• Protect important street vistas in town, such as:

– The entrance into town from the river bridge.

– Landmark buildings from across the railroad tracks.

– The Railroad Avenue streetscape with depot and tracks from points east and west.

• Continue to maintain the depot park on Railroad Avenue as a central public green.

• Keep the undeveloped green open space along Maloney Creek south of the tracks.

G4 Strengthen traditional development patterns.

• Whenever possible, site new commercial development along Railroad Avenue and the Old Cascade Highway.

• Orient commercial buildings in these locations squarely to the street, with facades aligned at the sidewalk edge.

• Whenever possible, site new residential development along established residential blocks.

• Conform with existing front and side yard setbacks in residential neighborhoods.

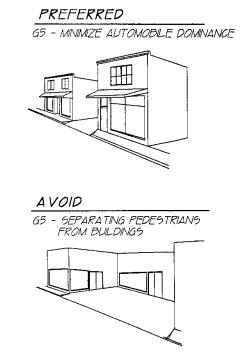

G5 Reinforce traditional parking patterns.

• Keep the pedestrian scale and continuity of the community by minimizing automobile dominance.

• Retain on-street parking in the historic commercial district; avoid off-street parking lots that separate pedestrian from building, and building from sidewalk.

• Where lot size allows, encourage residential parking to the rear of the common front building line.

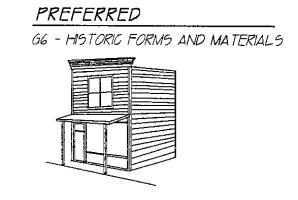

G6 Continue the use of historic building forms and materials.

• Maintain the building shapes, sizes, and roof configurations typically found in Skykomish, and repeat these forms in new construction.

– Rectangular primary form, with subordinate rectangular forms attached.

– One to three stories in height.

– Gabled, false-front, and pyramidal/hipped roof configurations.

• Perpetuate typical symmetrical facades with porches and central entrances oriented to the street.

• Continue the dominant use of horizontal wood siding as the primary exterior finish material; avoid synthetic siding.

• For roofing, continue the historical use of smooth-sawn wood shingles, or choose more recently traditional asphalt or metal finishes.

G7 Retain and adapt historic building for continued use.

• Seek new uses that are closely related to the original use.

• Respect the historic integrity of the building when redesigning for new use.

• Avoid adaptations that require radical alteration of historic building fabric.

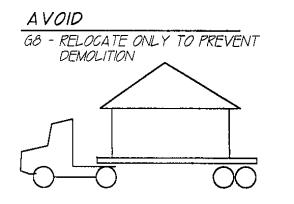

G8 Avoid historic building relocation except as a means of preventing loss.

• Because relocation destroys a building’s significant relationship to its site, consider this approach only in special cases.

• Ensure that the relocation site provides a context similar to that of the historic site.

• Provide evidence of a commitment to complete the relocation, and an appropriate rehabilitation plan.

• Treat relocation’s into the historic commercial district as new construction for purposes of design review.

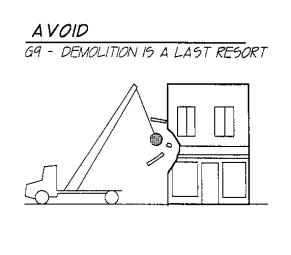

G9 Consider historic building demolition only as a last resort.

Because demolition of historic buildings is a severe and irreversible action, consider this option only when all other possibilities have been examined:

– Retaining and adapting the building for new use.

– Mothballing the building for future work.

– Incorporating the building into new development on its existing site.

– Relocating the building to an appropriate new site.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.080 Guidelines for commercial development.

(1) Overall Goal. The primary design goal for commercial development in Skykomish is to preserve and strengthen the early 20th century character of the business district, through appropriate treatment of existing buildings and through compatible new design.

(2) Guidelines. This section of guidelines applies to commercial projects within the historic commercial district and to designated commercial landmarks. The guidelines are presented as broad concepts in bold type, with explanatory subguidelines below.

Guidelines in this section begin with the letter “C” to indicate that they are guidelines that apply to commercial projects. “Historic” buildings are those 40 years of age or older, including designated landmarks. “Nonhistoric” buildings are those less than 40 years of age.

|

Designated Landmark: Maloney General Store Character-Defining Features |

|

|---|---|

|

– Location at Fifth Street and Railroad Avenue |

|

|

– Orientation to street and railroad tracks |

|

|

– Zero setback on both streets |

|

|

– Rectangular massing, with later additions |

|

|

– Gabled roof with false front, cornice detail |

|

|

– Hipped roof porch over sidewalk |

|

|

– Novelty wood siding |

|

|

– Storefront display windows, recessed entry |

|

|

– Other visible wood sash windows and entrances |

|

|

– Wall signage |

(a) Alteration of Historic Buildings (including maintenance, rehabilitation, and new additions).

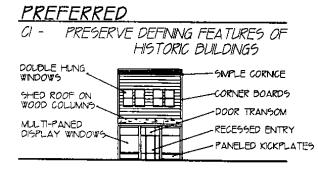

C1 Preserve all character-defining architectural features.

• Identify original or early character-defining features at the start of the project; including altered features that contribute to original design intent.

• Consider all of the following:

– Location and setting;

– Orientation and setback;

– Massing, including shape and size;

– Roof configuration, detail, and material;

– Porches or balconies;

– Windows and doors: proportions, arrangement, style, and materials;

– Siding and exterior paint color;

– Decorative trim elements;

– Distinctive signage;

– Early additions;

– Significant interior features and finishes for designated landmarks.

• Avoid damaging, removing, or unnecessarily altering any and all character-defining features.

C2 Repair rather than replace deteriorated features.

• Save as much historic fabric as possible, by patching, piecing, splicing, consolidating, or upgrading existing historic fabric.

• Replace features deteriorated beyond repair with materials that match in design, color, texture, and other visual qualities.

• Use physical or pictorial evidence to accurately replace missing features, consult the design review board for historic photo documentation.

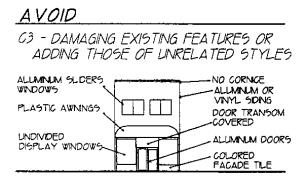

C3 Ensure that alterations are compatible with the authentic architectural character of the building.

• Do not create a false historical appearance with conjectural “historic” designs.

• When accurate replacement of missing features is impossible, create a compatible design that is readable as new.

• Minimize the visual impact of new mechanical or electrical equipment, handicapped access, and code compliance work.

C4 Treat original finishes with sensitivity.

• Avoid sandblasting historic wood siding to remove old paint, it will shorten the life of the wood.

• Do not cover up historic siding with vinyl, Z-brick, or other synthetic material.

• Paint with simple exterior color schemes that fall within the range of traditional early 20th century commercial buildings. See Appendix C.

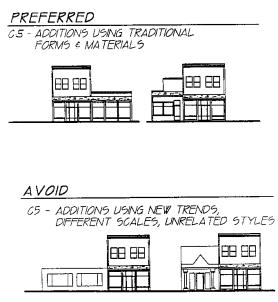

C5 Design new additions for compatibility with the building and block.

• Use the traditional buildings forms and materials of the historic commercial district.

• Keep new additions visually subordinate to historic buildings by locating them back from primary street facades.

• Create additions that are clearly recognizable as new construction, but in harmony with the historic building.

(b) Alteration of Nonhistoric Buildings (including exterior maintenance, remodeling, and new additions).

C6 Bring nonhistoric buildings into gradual consistency with the character of the historic commercial district.

• Use fence lines, hedges, or low walls along the sidewalk edge to reverse gaps in the streetscape created by deep setbacks and front parking lots.

• Through facade remodels, re-introduce traditional street-facing design components, as appropriate:

– Central entries;

– Flanking storefront display windows;

– Paneled kickplates;

– Double-hung windows at the second story;

– Covered sidewalks.

• Wherever possible, return to the use of horizontal wood siding, simple paint schemes, and wall signage traditional to the business district.

• Design new additions to nonhistoric buildings that are subordinate in scale, and that echo the massing and roof forms typical of the district.

(c) New Construction (new primary structures).

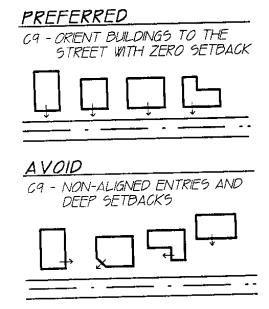

C9 Orient commercial buildings squarely to the street with facades aligned at the sidewalk edge.

• To prevent weakening of the streetscape, avoid orienting commercial buildings to the side.

• Provide public entrances on the primary street frontage to strengthen pedestrian interaction.

• Maintain and strengthen the traditional sense of pedestrian enclosure in the historic commercial district with zero setback along Railroad Avenue, Fifth Street, and Old Cascade Highway.

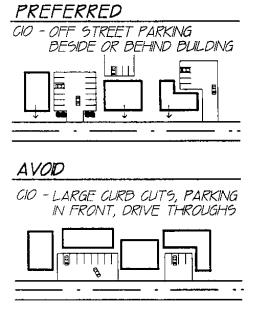

C10 Locate necessary off-street parking lots to the rear of buildings.

• To put pedestrians first and to maintain visual quality, do not locate parking lots or drive-throughs in front of commercial buildings.

• If on-street parking is inadequate, site small parking lots or drive-throughs to the rear of buildings.

• Where rear lots are not feasible, locate the lot to the side of the building with landscaping to screen it from the street.

• Minimize the number of driveways and curb cuts in the historic commercial district.

C11 Use traditional commercial shapes, sizes, and roof configurations.

• Limit building height to the predominant height of other buildings on the block.

• To bring back the continuous facade wall along Railroad Avenue, build new infill as nearly as possible to the full width of the lot.

• Design rooflines to reflect one of the traditional commercial roof configurations in Skykomish:

– Steeply pitched gable perpendicular to the street;

– Steeply pitched gable parallel to the street;

– Gable with false front;

– Hipped.

• For rear or side wings, use similar secondary roof types that are smaller and lower than the main roof ridge line.

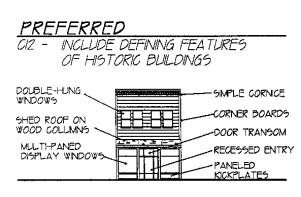

C12 Organize commercial building facades with traditional components.

• Consult with the design review board for facade design ideas from historic photos.

• Use updated versions of historic storefront elements typically found in Skykomish:

– Recessed entries;

– Paneled kickplates;

– Multi-paned display windows, commercial in scale;

– Transoms over doors;

– Shed or hipped roofs on wood posts over sidewalks.

• Include vertically-proportioned double-hung sash windows at the second-floor level in groups of one, two, or three.

• Consider balconies for two- or three-story structures.

• Accent the roofline with simple cornices, brackets, or dentil blocks.

C13 Employ exterior finish materials, details, color, and signage characteristic of early Skykomish.

• Stay within the traditional range of horizontal wood sidings: lapped, tongue-in-groove, shiplap.

• Avoid the use of synthetic siding material.

• Make generous use of wooden trim elements such as window and door surrounds, cornerboards, and cornices.

• Apply smooth-sawn wood shingle roofing, asphalt shingles similar in color and texture to wood, or metal roofing in a neutral color.

• Select paint color schemes that fall within the traditional commercial range for Skykomish, using just one base color and one or two trim colors. See Appendix C.

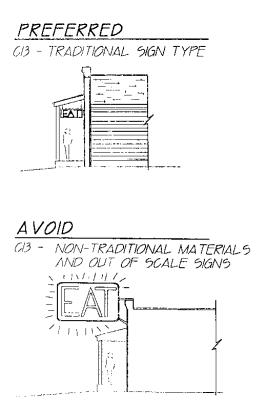

• Limit commercial signage to wall signs, hanging signs, or wall-mounted perpendicular signs, avoid the use of pole, monument, or roof-mounted signage.

• Integrate signage with the architectural design of the building in terms of placement, proportion, material, color, and lighting.

• In the historic commercial zone, follow the sign requirements set forth in SMC 18.50.100.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.090 Guidelines for residential development.

(1) Overall Goal. The primary design goal for residential development in Skykomish is to preserve and strengthen the early 20th century character of established residential blocks, through appropriate treatment of existing houses and through compatible new design.

(2) Guidelines. This section of guidelines applies to residential projects within the historic commercial district and to designated residential landmarks. The guidelines are presented as broad concepts in bold type, with explanatory subguidelines below.

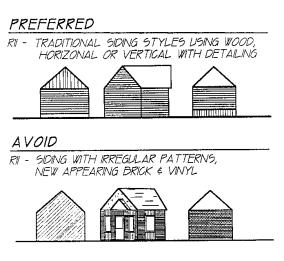

Guidelines in this section begin with the letter “R” to indicate that they are guidelines that apply to residential projects. “Historic” buildings are those 40 years of age or older, including designated landmarks. “Nonhistoric” buildings are those less than 40 years of age.

|

Designated Landmark: Teachers’ Cottage Character-Defining Features |

|---|

|

– Location adjacent to school |

|

– Orientation to Sixth Street with typical residential setback |

|

– Distinctive footprint and cross-gabled roof configuration |

|

– Front and rear recessed porches |

|

– Narrow gauge, lapped horizontal siding |

|

– Double-hung sash with four or six-over-one lights, arranged in single, double, and triple groups |

|

– Multi-paned front door with sidelights |

|

– Vertical board trim in gables and other roofline details |

|

– Interior features: spatial configuration, staircase components, all woodwork |

(a) Alterations to Historic Residences (including maintenance, rehabilitation, and new additions).

R1 Preserve all character-defining architectural features.

• Identify original or early character-defining features at the start of the project; including altered features that contribute to original design intent.

• Consider all of the following:

– Location, setting, and orientation;

– Setback, front and side yards, and notable landscape features;

– Massing, including shape and size;

– Roof configuration, detail, dormers, and material;

– Front porches;

– Windows and doors: proportions, arrangement, style, and materials;

– Siding type and exterior paint color;

– Decorative trim elements;

– Early additions, garages, or other secondary structures;

– Significant interior features and finishes for designated landmarks.

• Avoid damaging, removing, or unnecessarily altering any and all character-defining features.

R2 Repair rather than replace deteriorated features.

• Save as much historic fabric as possible, by patching, piecing, splicing, consolidating, or upgrading existing historic fabric.

• Replace features deteriorated beyond repair with materials that match in design, color, texture, and other visual qualities.

• Use physical or pictorial evidence to accurately replace missing features; consult the design review board for historic photo documentation.

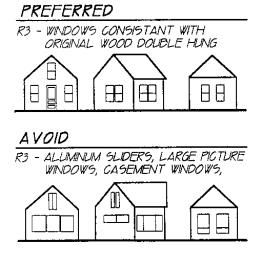

R3 Ensure that alterations are compatible with the authentic architectural character of the house.

• Avoid common changes that erode historic character, such as:

– Replacing wooden porch elements with wrought iron;

– Changing the shape and proportions of windows;

– Adding shutters where none existed;

– Removing window or door trim;

– Replacing a paneled glazed door with a flat hollow-core door;

– Enclosing an open front porch.

• Do not create a false historical appearance with conjectural “historic” designs.

• When accurate replacement of missing features is impossible, create a compatible design that is readable as new.

R4 Treat original finishes with sensitivity.

• Avoid sandblasting historic wood siding to remove old paint, it shortens the life of the wood.

• Do not cover up historic siding with vinyl, Z-brick, or other synthetic material.

• Paint with simple exterior color schemes that fall within the range of traditional early 20th century domestic architecture. See Appendix C.

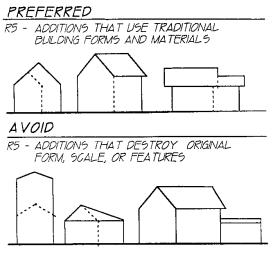

R5 Design new additions for compatibility with the main dwelling and the surrounding neighborhood.

• Use the traditional residential building forms and materials of Skykomish.

• Keep new additions visually subordinate to the historic house by locating them well back from the primary street.

• Create additions that are clearly recognizable as new construction, but which harmonize with the historic house.

(b) Alterations to Nonhistoric Residences (including exterior maintenance, remodeling, and new additions).

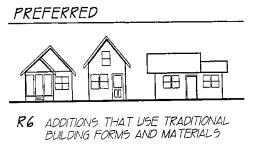

R6 Bring nonhistoric houses into general consistency with the character of Skykomish residential neighborhoods.

• Establish simple front yard landscaping and enhance the streetscape with low wooden fencing or plant materials along the sidewalk edge.

• Through exterior remodels, re-introduce traditional primary facade design components, as appropriate:

– Central entries facing the street;

– Flanking vertically-proportioned windows;

– Windows at the second story;

– Open, raised front porches with hipped or gabled roofs.

• Wherever feasible, return to the use of horizontal or wood-shingle siding and traditional exterior paint schemes.

• Apply smooth-sawn wood shingle roofing, asphalt shingles similar in color and texture to wood, or metal roofing in a neutral color.

• Design new additions that are subordinate in scale, well set back from the front of the main house, and typical of residential massing and roof forms in Skykomish.

(c) New Construction (new primary residences).

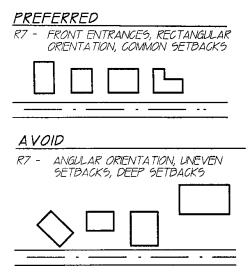

R7 Orient houses to the street or railroad tracks, and align facades with the dominant setback on the block.

• To strengthen the streetscape, avoid unusually deep setbacks and houses oriented to the side.

• Provide front entrances on the primary street frontage to preserve a pedestrian-friendly feeling.

• Establish simple front yard landscaping and enhance the streetscape with low wooden fencing or plant materials along the sidewalk edge.

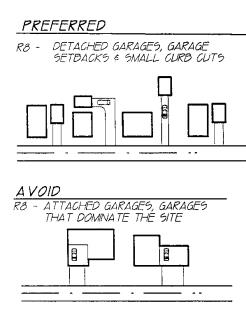

R8 Provide on-street residential parking or off-street parking to the rear of houses.

• To reinforce neighborhood tradition, provide detached garages to the rear of residential lots.

• Set back all garages, attached or detached, so that cars parked outside will not project beyond the front building line.

• Keep curb cuts for residential driveways as narrow as possible to preserve pleasant, walkable streets.

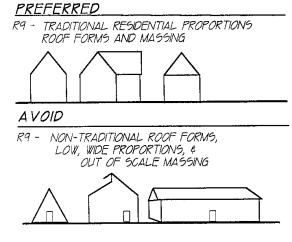

R9 Use traditional residential shapes, sizes, and roof configurations.

• Limit house height to the predominant height of other houses on the block, generally one to two stories.

• Use traditional rectangular massing, with dimensions and proportions found locally.

• Design rooflines to reflect one of the traditional residential roof configurations in Skykomish:

– Steep or moderately-pitched gable perpendicular to the street;

– Lateral gable parallel to the street;

– Cross-gabled;

– Hipped/pyramidal.

• Incorporate shed-roofed dormers for upper story light.

• For rear or side wings, use similar massing and similar roof types that are smaller and lower than the main roof ridge line.

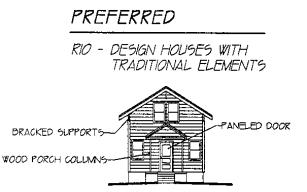

R10 Design house facades with traditional components.

• Consult with the design review board for facade design ideas from historic photos; use updated versions of these features in new design.

• Consider including a raised front porch with a roofline that echoes the main roof, and porch decks, simple railings, and support posts of wood.

• Alternatively, add a gabled, hipped, or shed roofed hood with bracketed supports over the front doorway.

• Use central or offset front entrances, with paneled and glazed doors.

• Install vertically-proportioned wood windows, possibly paired, arranged symmetrically on first and second stories.

• Accent the roofline with historically-based details, such as decorative bracketed supports in the gable and exposed rafter tails along the eaves.

R11 Employ exterior finish materials, details, and color schemes characteristic of early Skykomish residences.

• Stay within the traditional range of residential wood sidings: clapboard, tongue-in-groove, and shiplap horizontal, or wood shingle siding.

• Avoid the use of synthetic siding material.

• Make use of wooden trim elements such as window and door surrounds, cornerboards, and roofline detail.

• Apply smooth-sawn wood shingle roofing, asphalt shingles similar in color and texture to wood, or metal roofing in a neutral color.

• Paint all residential wood exteriors with color schemes that fall within the traditional residential range for Skykomish, using just one base color and one or two trim colors. See Appendix C.

• Apply smooth-sawn wood shingle roofing, asphalt shingles similar in color and texture to wood, or metal roofing in a neutral color.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.100 Guidelines for institutional development.

(1) Overall Goal. The primary design goal for institutional development in Skykomish is to preserve and enhance landmark buildings significant to the history of the whole community, and to encourage new civic design that adds to the town’s quality of life.

(2) Guidelines. This section of guidelines applies to public and institutional projects within the historic commercial district and to designated public/institutional landmarks. The guidelines are presented as broad concepts in bold type, with explanatory subguidelines below.

Guidelines in this section begin with the letter “P” to indicate that they are guidelines that apply to public and institutional projects. “Historic” buildings are those 40 years of age or older, including designated landmarks. “Nonhistoric” buildings are those less than 40 years of age.

|

Designated Landmark: Skykomish School Character-Defining Features |

|---|

|

– Location and orientation to Sixth Street |

|

– Setback and remnant landscape features |

|

– Dimensions and massing |

|

– Flat roof configuration |

|

– Fenestration pattern, including placement, groupings, multi-paned sash |

|

– Formal high school and grade school entrances with signage |

|

– Exterior concrete surfaces with Art Moderne details in relief |

|

– Interior features, including: spatial configuration of corridors and classrooms; staircases; built-in planters; all woodwork; classroom cabinetry; library bookshelves; sliding slate chalkboards; principal’s office; clock system; and gymnasium stage, wall finish, balcony, risers, benches, and pipe railings |

(a) Alteration of Historic Buildings (including exterior maintenance, rehabilitation, and new additions).

P1 Preserve all character-defining architectural features.

• Identify original or early character-defining features at the start of the project; including altered features that contribute to original design intent.

• Consider such elements as: location, setting, and orientation; setback and notable landscape features; massing, roof configuration, detail, and material; formal entrances, window proportions, arrangement, style, and materials; exterior finish and paint color, decorative trim elements; early additions, and other secondary structures; significant interior features and finishes for designated landmarks.

• Avoid damaging, removing, or unnecessarily altering any and all character-defining features.

P2 Repair rather than replace deteriorated features.

• Save as much historic fabric as possible, by patching, piecing, splicing, consolidating, or upgrading existing historic fabric.

• Replace features deteriorated beyond repair with materials that match in design, color, texture, and other visual qualities.

• Use physical or pictorial evidence to accurately replace missing features; consult the design review board for historic photo documentation.

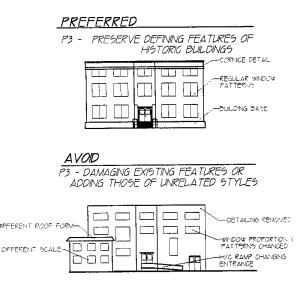

P3 Ensure that alterations are compatible with the authentic architectural character of the building.

• Avoid common mistakes that erode historic character, such as:

– Rearranging and redesigning original door and window openings;

– Damaging an original formal entrance with handicapped access;

– Removing characteristic detailing, exterior or interior;

– Making additions that obscure important architectural features;

– Partitioning significant interior spaces.

• Do not create a false historical appearance with conjectural “historic” designs.

• When accurate replacement of missing features is impossible, create a compatible design that is readable as new.

P4 Treat original finishes with sensitivity.

• Avoid sandblasting historic wood siding to remove old paint, it shortens the life of the wood.

• Do not cover up historic siding with vinyl, or any other synthetic material.

• Paint with simple exterior color schemes that fall within the range of traditional early 20th century public architecture. See Appendix C.

• Do not paint over natural finished interior woodwork.

• Avoid unnecessary replacement of original interior lath and plaster.

P5 Design new additions for compatibility with the main building and the surrounding neighborhood.

• Use the traditional building forms and materials of Skykomish.

• Keep new additions visually subordinate to the historic structure by locating them well back from the primary street.

• Create additions that are clearly recognizable as new construction, but which harmonize with the historic building.

|

Designated Landmark: Masonic Hall Character-Defining Features |

|---|

|

– Location south of tracks and orientation to Old Cascade Highway |

|

– Overall two-story rectangular massing with subordinate entry and kitchen additions |

|

– Steeply-pitched gable roof configuration, with exposed rafter tails and brackets at the gable overhang |

|

– Horizontal shiplap siding |

|

– Double-hung windows, single and paired |

|

– Early metal fire escape |

|

– Woodshed dependency at rear |

|

– Interior features, including: spatial configuration of all rooms, flush board walls and flooring, ticket window on enclosed porch, kitchen cabinetry in northwest corner, staircase, anteroom woodwork, raised platform and doors in meeting hall, Parker Room knotty pine |

(b) Alteration of Nonhistoric Buildings (including exterior maintenance, remodeling, and new additions).

P6 Bring nonhistoric buildings into gradual consistency with the character of the historic commercial district.

• Through exterior remodels, re-introduce some of the traditional design components of public architecture, as appropriate.

– Landscaped setting;

– Prominent formal entrance facing the street;

– Generous symmetrically-arranged windows;

– Overall sense of style.

• Wherever possible, return to the use of horizontal wood siding, simple but distinctive paint schemes, and modest wall signage.

• Design new additions to nonhistoric buildings that are subordinate in scale, and that echo the massing and roof forms typical of the district.

|

Designated Landmark: Great Northern Depot Character-Defining Features |

|---|

|

– Location on Railroad Avenue and direct orientation to tracks |

|

– Park setting |

|

– Simple rectangular massing with projecting bay window trackside |

|

– Gabled roof with broad overhanging eaves |

|

– All early wooden doors and windows |

|

– Horizontal wood siding, narrow gauge lapped and shiplap |

|

– Skykomish sign |

(c) New Construction (new primary structures).

P7 Orient new public and institutional buildings to the street and provide a prominent public entry.

• Base the setback on the predominant setback of neighboring properties.

• Provide formal public entrances on the primary street frontage to strengthen pedestrian interaction.

• Whenever possible, site new public buildings in prominent locations so they serve as community focal points.

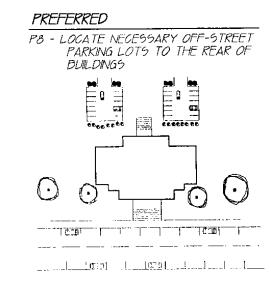

P8 Locate necessary off-street parking lots to the rear of buildings.

• To put pedestrians first, avoid locating parking lots in front of public buildings.

• If on-street parking is inadequate, site small parking lots to the rear of buildings.

• Where rear lots are not feasible, locate the lot to the side of the building with landscaping to screen it from the street.

P9 Use massing and roof configurations traditional to public architecture in Skykomish.

• Consider the massing and roof forms of adjacent historic buildings.

• Choose building shapes and sizes from among the wide range of public and institutional structures in Skykomish.

• Design rooflines to reflect one of the traditional roof configurations in Skykomish:

– Steep to medium-pitched gable for wood framed buildings;

– Hipped for wood framed buildings;

– Flat for masonry buildings.

• For rear or side wings, use similar secondary roof types that are smaller and lower than the main roof ridge line.

P10 Organize building facades with the traditional components of public architecture.

• Be respectful of adjacent historic buildings.

• Express a clear overall concept or style on the building’s exterior.

• Give formal front entrances special emphasis and detailing.

• Include generously proportioned windows as an integral element of facade design.

• Give the roofline visual distinction through the use of architectural focal points.

P11 Employ exterior finish materials, details, color, and signage characteristic of public buildings in early Skykomish.

• Be respectful of adjacent historic structures.

• Stay within the traditional range of exterior finishes: horizontal wood siding, or smooth surfaced concrete.

• Avoid the use of synthetic siding material.

• Apply smooth-sawn wood shingle roofing, asphalt shingles similar in color and texture to wood, or metal roofing in a neutral color.

• Select paint color schemes that fall within a traditional range for Skykomish. See Appendix C.

• Limit signage on public buildings to wall signs or hanging signs; avoid the use of pole, monument, or roof-mounted signage.

• Integrate signage with the architectural design of the building in terms of placement, proportion, material, color, and lighting.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)

18.90.110 Guidelines for other site work.

(1) Overall Goal. The primary design goal for other site work in Skykomish is to further reinforce and enhance the historic character of the community.

(2) Guidelines. This section of guidelines applies to other kinds of minor site work within the historic commercial district and at designated landmarks. The guidelines are presented as broad concepts in bold type, with explanatory subguidelines below.

Guidelines in this section begin with the letter “O” to indicate that they are guidelines that apply to other site work.

O1 Encourage the creation and maintenance of landscaping.

• Wherever possible, preserve existing trees on private property and in the public right-of-way.

• Create landscaped borders at the sidewalk edge of residential properties.

• Select climate-appropriate plant materials or native species that require minimal maintenance. See Appendix B.

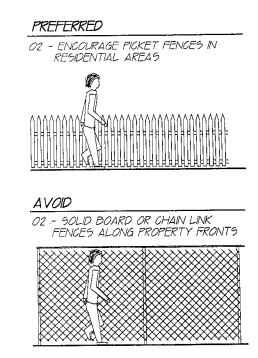

O2 Encourage the use of historic fencing in residential areas.

• To re-introduce historic character, erect wooden picket fences or wire garden fences at the sidewalk or roadway edge of residential properties.

• Along front property lines, limit fences to three or four feet in height, as seen in historic photos.

• Avoid solid board fences and chain link fences along front property lines.

O3 Screen all trash receptacles from public view.

• Site all receptacles in unobtrusive locations.

• For commercial receptacles, provide a minimum 15-foot setback from any residential property boundary.

• Use gated solid walls, fences, or landscaping to screen commercial dumpsters.

O4 Screen exterior mechanical devices from public view.

• Site all heating, cooling, ventilating equipment and propane tanks in unobtrusive locations.

• If necessary, further screen such devices with fences or landscaping.

O5 Minimize the visual impact of antennas and satellite dishes from the public way.

• Meet the performance standards set forth in SMC 18.45.070(6).

O6 Keep outdoor lighting simple and in character with the community.

• Design simple street lights of appropriate scale and low intensity.

• Shield outdoor lighting on private lots so that direct illumination is confined to the property boundaries.

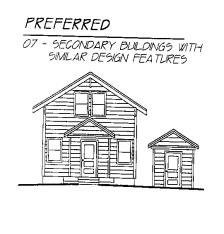

O7 Create secondary buildings which reflect the design of the primary building and contribute to the character of the community.

• For garages, storage sheds, and wood sheds, repeat the traditional forms and roof configurations found in Skykomish.

• Use wood siding or other traditional cladding material; avoid synthetic and metal siding.

• Locate secondary structures behind the facade of the primary building.

(Ord. 259 § 3, 1997; Ord. 235, 1995)